War Movies That Are Close To Reality

Best Presentation of a Training Camp: “Full Metal Jacket” (1987)

Though this one seems pretty expected, no other movie has depicted a boot camp better than Full Metal Jacket. Many people bash R. Lee Ermey for making it big by playing himself in almost every movie, but his appearance as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman in the said film was indubitably stellar. Ermey had actually served in the Marines, and Stanley Kubrick realized that letting him improvise would make the movie a classic. That’s exactly what the actor did, and most of his dialogues were written by him. The result was a success. Ermey managed to make a comical drill instructor look like the most macho character an action film has ever produced. He had done the same thing almost 10 years prior to Full Metal Jacket’s release, in the film The Boys In Company C. Ermey’s portrayal was both hilarious and scary, and since then, no other actor has managed to portray a drill sergeant better than him.

Best Depiction of Helplessness: “Das Boot” (1981)

Sooner or later in the military, you find yourself stuck inside some big metal machine or other, reflecting on how soft and vulnerable your own body is underneath all that steel and armor, and how helpless you are to control what happens to it at that moment. In a submarine, death hovers always a few feet away, on all sides, creating the perfect setting for Wolfgang Petersen’s masterwork, which follows a single patrol of a German U-Boat in World War II and stretches that helpless tension and anxiety across two and a half nearly unbearable hours (in the shortest of the film’s many cuts). Watch it in one sitting, in German with subtitles. You’ll need a drink afterward.

Best Deployment Phone Call Home: “Jarhead” (2005)

Telephones on deployment are evil. There should be no phones at war. Let me explain.

Think of it: You take a bunch of nineteen-year-olds, train them to fight, teach them to put aside all the drama and nonsense of their personal lives, ship them off to a war zone where the entirety of their daily existence is focused on their jobs, and then you inject all that drama and nonsense right back into their war zone heads on a daily basis courtesy of the telephone trailers found on every modern Forward Operating Base. (Make that telephone trailers featuring frequent call drops and a lengthy time lag so that it feels like you’re trading messages over a radio – “I love you, over.”) What you get is a bunch of distracted nineteen-year-olds who are supposed to be thinking about their jobs spending their time obsessing about their nineteen-year-old drama instead, thinking about their last emotionally fraught call home and counting the hours until they can get back to the trailer for today’s fraught phone call to rehash whatever yesterday’s drama was about.

Jake Gyllenhaal’s call home in “Jarhead,” in which he finally gets on the phone with his girlfriend for the first time in weeks and immediately vomits jealous obsession all over her before getting cut off, is the perfect specimen. It may have only lasted about thirty seconds, but that’s pretty much what half the real phone calls are like, just longer and more painful to overhear. I love soldiers to death, loved working with them and doing my best to take care of them. But they need to be kept away from phones overseas. When you go to war, you should go to war and be at war, and write letters home instead.

Best Portrait of Lost Innocence: “Gallipoli” (1981)

The First World War broke the West’s faith in itself, the effects of that disillusionment persisting in our culture today. It’s appropriate, then, that a film about that war offers what’s for my money the best portrayal of youthful naivete meeting its end in war. This Australian film follows the exploits of two young men from the rural west of that country, one an idealist played by Mark Lee, the other a streetwise cynic played by a young Mel Gibson, and their eventual enlistment in the Australian Army and participation in the failed Dardanelles Campaign against the Ottoman Empire. This film might have been simply patronizing in its treatment of the values of a genuinely simpler time, but the sympathy with which it handles these young men’s romanticism toward war lends greater power to its inevitable conclusion: not a good death, in the old sense, or even a bad or tragic one, but just a sudden, offhanded, unceremonious end to your existence.

More inCommunity

-

`

A Veteran’s Open Letter To The Prince Of Cambridge

If you were born a prince, like a famous Prince of Cambridge, you would have a lot of options for your...

June 5, 2023 -

`

You Must Appreciate the Amazing Growth of the Tulsa Community Foundation

The Tulsa Community Foundation (TCF) is a charitable organization which was founded on the 30th of December 1998 by a banker,...

June 5, 2023 -

`

ELDERBERRIES: Learn about These Powerful, Immune-Strengthening Tart Little Fruits!

What would you do if someone handed you a capsule that could regulate your blood sugar level, help you lose weight,...

June 5, 2023 -

`

Here Is Why Lucy Kennedy Should Be Your Inspiration

For normal people like us, celebrities (or famous people, for that matter) offer a window to the limitless possibilities which we...

June 5, 2023 -

`

If You’re Among The Health-Watchers, You Should Probably Know About Pre-Diabetes

If you’re an adult and consider yourself sufficiently aware, you know what diabetes is. The disease is so common that even...

June 2, 2023 -

`

Motivation Isn’t Enough to Get You to the Finish Line; You Need Discipline!

Motivation is the intrinsic spirit to undertake a challenging task. It is the positive enforcement that comes from within and keeps...

June 2, 2023 -

`

Gardening and Green Activities: a Definite Solution for Your Anxiety Attacks!

If you are not fond of nature and nurturing plants, you may be shaking your head at the idea of gardening....

May 30, 2023 -

`

Health Benefits Of Eating Beets You Probably Didn’t Know

Beets have gained much importance as a healthy low-calorie food option in many diet charts. It has become one of the...

May 30, 2023 -

`

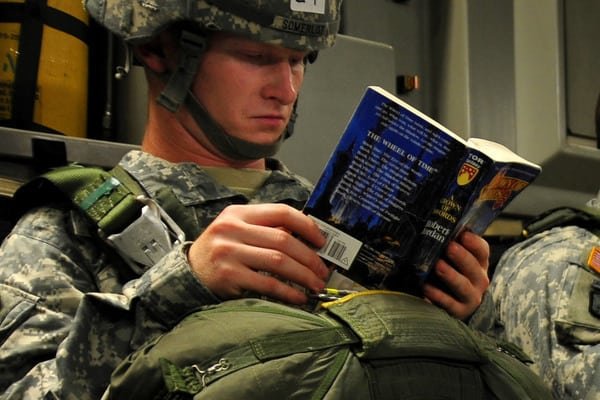

Best Books Ever Written About War That Every Man Should Read

Every military service member needs his daily dose of knowledge and skill enhancement, inspiration and motivation. And reading some books about...

May 30, 2023

You must be logged in to post a comment Login